Warehouses Closed June 6-13 For Exclusive Event

Button, Button, Who's Got 'Em? The Button Museum, That's Who!

Button, Button, Who's Got 'Em? The Button Museum, That's Who!

Is there a jar of buttons in your sewing room? Here's a story about a small museum with a big history.

Pearl buttons are cooler than plastic. And not just because they bring a tiny gleam to the dresses and shirts onto which they’re stitched. If you put your pearl button up to your cheek and then do the same with a plastic one, you’ll notice an actual difference in temperature.

That’s just one of the things I learned when I visited the Pearl Button Museum in Muscatine, Iowa. I also discovered that pearl buttons are heavier than plastic, and that they make a different sound as they slide through your fingers. As a transplanted Californian who spent her childhood obsessively collecting shells, I’d always assumed that lustrous, white mother-of-pearl buttons came from the ocean. But there was a time when 37 percent of the world’s buttons (in 1905, that was 1.5 billion buttons) came from the glossy inner surfaces of freshwater mollusk shells harvested by citizens of this small town on the Mississippi River.

As a transplanted Californian who spent her childhood obsessively collecting shells, I’d always assumed that lustrous, white mother-of-pearl buttons came from the ocean. But there was a time when 37 percent of the world’s buttons (in 1905, that was 1.5 billion buttons) came from the glossy inner surfaces of freshwater mollusk shells harvested by citizens of this small town on the Mississippi River.

Muscatine’s downtown today is a sleepy place, with brick buildings on a quiet main street just a block from the river. The Pearl Button Museum isn’t large: on a single floor you can see the flat-bottom boats used to harvest mussels and the machinery to cut, drill, and polish the button “blanks.” You can try your hand at sewing buttons on a card, dip your fingers in buckets of buttons, and count out a gross (144 buttons) with a specially indented wooden paddle.

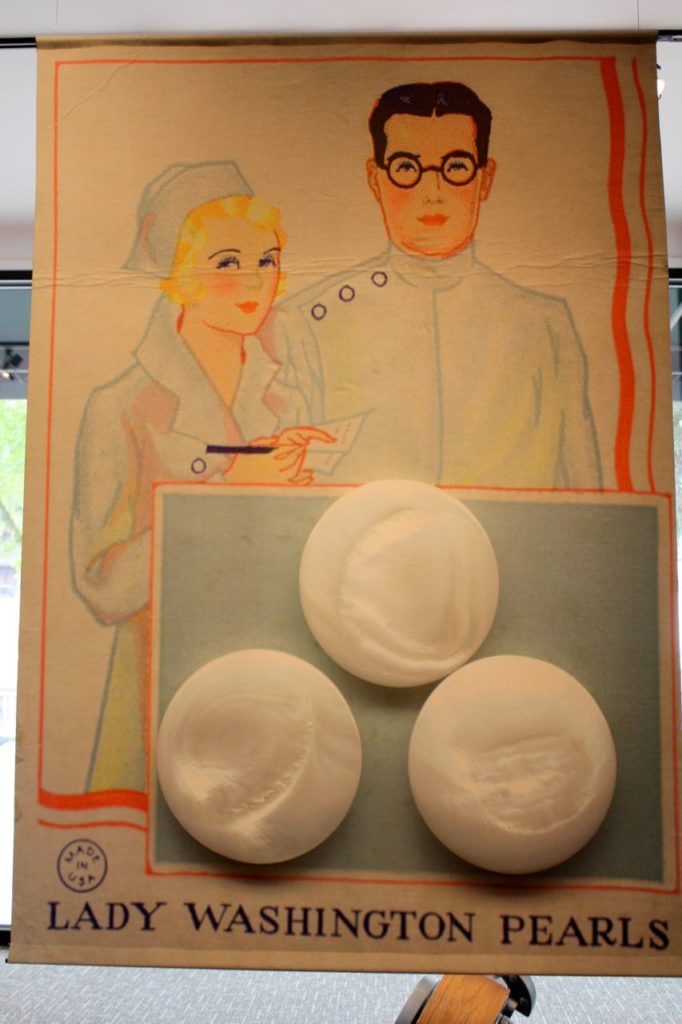

Exhibits include equipment for clamming and making buttons. Posters of button cards hang from the ceiling.

Exhibits include equipment for clamming and making buttons. Posters of button cards hang from the ceiling.

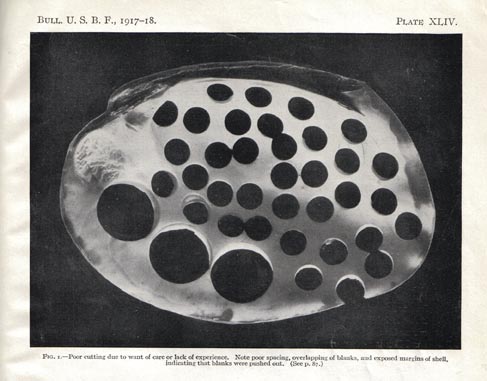

Historical photos provide insight into a town in which half the workforce (including many children) worked in the button industry. After the mussels were collected—a process known as clamming—men and women worked in camps along the water heating and opening the mussels, removing the meat and any irregular-shaped freshwater pearls (called “slugs”) they were lucky enough to find. Hundreds of men worked in the cutting shops, cutting blanks—the basic shape of the button—from the shiny inner surface of the shells, while others operated machinery that carved designs on the blanks and drilled the holes. Women shaped fancier buttons against rotating emery wheels and removed the dark surface or “bark” on buttons by machine; sorted buttons by color, iridescence, and size; and sewed them onto cards. The dozens of factories in town ranged from the Hawkeye Button Company that in 1911 employed 800 people and had offices in New York and St. Louis to myriad mom-and-pop operations: men cut and drilled buttons in garages and sheds behind their homes while women sorted and sewed them on cards in their living rooms.

Image courtesy of the Muscatine History and Industry Center

Image courtesy of the Muscatine History and Industry Center

The riverbanks and alleys of Muscatine were piled high with leftover shells. Tons were crushed to create street surfaces, fertilizer, stucco, and even gravel for the bottom of fish bowls. Kristin McHugh-Johnston, former director of the Muscatine History and Industry Center, said that when she worked in her garden eight blocks from the river, she still sometimes dug up a shell from which buttons were cut. While Muscatine takes pride in its button heritage—a 28-foot tall bronze sculpture of a “clammer” hoists his clamming forks above the downtown riverfront—museum displays acknowledge that creating these pearl lovelies was a dirty, dangerous, and low-paying business. Advances in button-making machinery ensured Muscatine’s reign as the “Pearl Button Capitol of the World” for decades, but eventually Mississippi mussels were fished to scarcity and freshwater and ocean shells had to be shipped to Muscatine for cutting. Plastic buttons, zippers, changes in fashion, and foreign competition led to a decline in the industry. The last Muscatine pearl button was cut in 1967, though production began to slow in the 1930s. Just one button company remains in Muscatine today, producing resin buttons.

While Muscatine takes pride in its button heritage—a 28-foot tall bronze sculpture of a “clammer” hoists his clamming forks above the downtown riverfront—museum displays acknowledge that creating these pearl lovelies was a dirty, dangerous, and low-paying business. Advances in button-making machinery ensured Muscatine’s reign as the “Pearl Button Capitol of the World” for decades, but eventually Mississippi mussels were fished to scarcity and freshwater and ocean shells had to be shipped to Muscatine for cutting. Plastic buttons, zippers, changes in fashion, and foreign competition led to a decline in the industry. The last Muscatine pearl button was cut in 1967, though production began to slow in the 1930s. Just one button company remains in Muscatine today, producing resin buttons.

Today, most pearl buttons are made in Asia from clam, mussel, agoya, and abalone shells. Designs are cut with lasers and dyed buttons often receive a polyester coating to protect their surface. Elaborate fusions of rhinestones, plastics, and pearl create elegant buttons, unimaginable in Muscatine’s pearl button heyday.

Today, most pearl buttons are made in Asia from clam, mussel, agoya, and abalone shells. Designs are cut with lasers and dyed buttons often receive a polyester coating to protect their surface. Elaborate fusions of rhinestones, plastics, and pearl create elegant buttons, unimaginable in Muscatine’s pearl button heyday.

A reproduction poster of a button card.

A reproduction poster of a button card.

Still, when I’m at a flea market or antique shop and happen upon those simple, shiny vintage disks, I feel a thrill of pleasure: finding a Blue Bonnet or Lucky Day brand button card adorned with a drawing of a laughing baby or the placket of a manly shirt reminds me of all that I’ve learned about pearl buttons (and about my adopted state). I hold the card to my cheek and the cool surface of the lustrous discs assures me that this is the real thing.

This story originally appeared on Etsy's blog on June 7, 2010.

Comments